What Is the Quantity Arrived at an Iteration Do Again

Lookout man Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Sentinel it together with the written tutorial to deepen your agreement: For Loops in Python (Definite Iteration)

This tutorial will show you lot how to perform definite iteration with a Python for loop.

In the previous tutorial in this introductory series, you learned the following:

- Repetitive execution of the same block of code over and over is referred to equally iteration.

- There are two types of iteration:

- Definite iteration, in which the number of repetitions is specified explicitly in advance

- Indefinite iteration, in which the code block executes until some status is met

- In Python, indefinite iteration is performed with a

whileloop.

Here'southward what you lot'll comprehend in this tutorial:

-

Yous'll offset with a comparison of some different paradigms used past programming languages to implement definite iteration.

-

Then you will learn nigh iterables and iterators, two concepts that form the basis of definite iteration in Python.

-

Finally, you lot'll tie it all together and learn about Python'southward

forloops.

A Survey of Definite Iteration in Programming

Definite iteration loops are ofttimes referred to every bit for loops because for is the keyword that is used to introduce them in most all programming languages, including Python.

Historically, programming languages have offered a few assorted flavors of for loop. These are briefly described in the following sections.

Numeric Range Loop

The about basic for loop is a simple numeric range argument with start and cease values. The exact format varies depending on the language but typically looks something similar this:

for i = i to 10 < loop body > Here, the body of the loop is executed ten times. The variable i assumes the value one on the get-go iteration, ii on the 2d, and then on. This sort of for loop is used in the languages Basic, Algol, and Pascal.

Three-Expression Loop

Some other form of for loop popularized by the C programming language contains iii parts:

- An initialization

- An expression specifying an ending status

- An activity to be performed at the end of each iteration.

This type of loop has the following form:

for ( i = i ; i <= 10 ; i ++ ) < loop body > This loop is interpreted as follows:

- Initialize

ito1. - Continue looping as long as

i <= 10. - Increase

ibyanesubsequently each loop iteration.

Iii-expression for loops are popular considering the expressions specified for the three parts can be well-nigh annihilation, so this has quite a chip more flexibility than the simpler numeric range form shown above. These for loops are also featured in the C++, Java, PHP, and Perl languages.

Drove-Based or Iterator-Based Loop

This type of loop iterates over a collection of objects, rather than specifying numeric values or conditions:

for i in < collection > < loop body > Each time through the loop, the variable i takes on the value of the next object in <collection>. This type of for loop is arguably the most generalized and abstract. Perl and PHP as well support this blazon of loop, but it is introduced by the keyword foreach instead of for.

The Python for Loop

Of the loop types listed above, Python only implements the last: collection-based iteration. At first blush, that may seem similar a raw deal, merely rest assured that Python's implementation of definite iteration is and so versatile that you won't end up feeling cheated!

Shortly, you lot'll dig into the guts of Python'due south for loop in detail. But for at present, let's start with a quick prototype and example, just to go acquainted.

Python'south for loop looks like this:

for < var > in < iterable > : < statement ( s ) > <iterable> is a drove of objects—for case, a list or tuple. The <statement(due south)> in the loop body are denoted by indentation, every bit with all Python command structures, and are executed once for each item in <iterable>. The loop variable <var> takes on the value of the next chemical element in <iterable> each time through the loop.

Here is a representative example:

>>>

>>> a = [ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' ] >>> for i in a : ... impress ( i ) ... foo bar baz In this example, <iterable> is the list a, and <var> is the variable i. Each time through the loop, i takes on a successive particular in a, so print() displays the values 'foo', 'bar', and 'baz', respectively. A for loop like this is the Pythonic way to process the items in an iterable.

Simply what exactly is an iterable? Before examining for loops farther, it will be beneficial to delve more deeply into what iterables are in Python.

Iterables

In Python, iterable ways an object can be used in iteration. The term is used as:

- An describing word: An object may be described equally iterable.

- A substantive: An object may be characterized equally an iterable.

If an object is iterable, information technology tin can exist passed to the built-in Python office iter(), which returns something called an iterator. Yes, the terminology gets a scrap repetitive. Hang in in that location. It all works out in the terminate.

Each of the objects in the post-obit example is an iterable and returns some blazon of iterator when passed to iter():

>>>

>>> iter ( 'foobar' ) # String <str_iterator object at 0x036E2750> >>> iter ([ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' ]) # Listing <list_iterator object at 0x036E27D0> >>> iter (( 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' )) # Tuple <tuple_iterator object at 0x036E27F0> >>> iter ({ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' }) # Gear up <set_iterator object at 0x036DEA08> >>> iter ({ 'foo' : ane , 'bar' : 2 , 'baz' : 3 }) # Dict <dict_keyiterator object at 0x036DD990> These object types, on the other hand, aren't iterable:

>>>

>>> iter ( 42 ) # Integer Traceback (nearly contempo call final): File "<pyshell#26>", line 1, in <module> iter ( 42 ) TypeError: 'int' object is not iterable >>> iter ( 3.i ) # Bladder Traceback (most recent call last): File "<pyshell#27>", line ane, in <module> iter ( 3.1 ) TypeError: 'bladder' object is not iterable >>> iter ( len ) # Built-in role Traceback (most contempo call terminal): File "<pyshell#28>", line 1, in <module> iter ( len ) TypeError: 'builtin_function_or_method' object is not iterable All the information types you have encountered and then far that are collection or container types are iterable. These include the string, list, tuple, dict, set, and frozenset types.

But these are by no means the only types that y'all tin iterate over. Many objects that are built into Python or defined in modules are designed to be iterable. For example, open files in Python are iterable. As you will encounter soon in the tutorial on file I/O, iterating over an open file object reads data from the file.

In fact, virtually any object in Python can be fabricated iterable. Fifty-fifty user-defined objects can be designed in such a style that they can exist iterated over. (You will find out how that is washed in the upcoming article on object-oriented programming.)

Iterators

Okay, now you lot know what it means for an object to exist iterable, and yous know how to use iter() to obtain an iterator from it. Once you've got an iterator, what can you do with it?

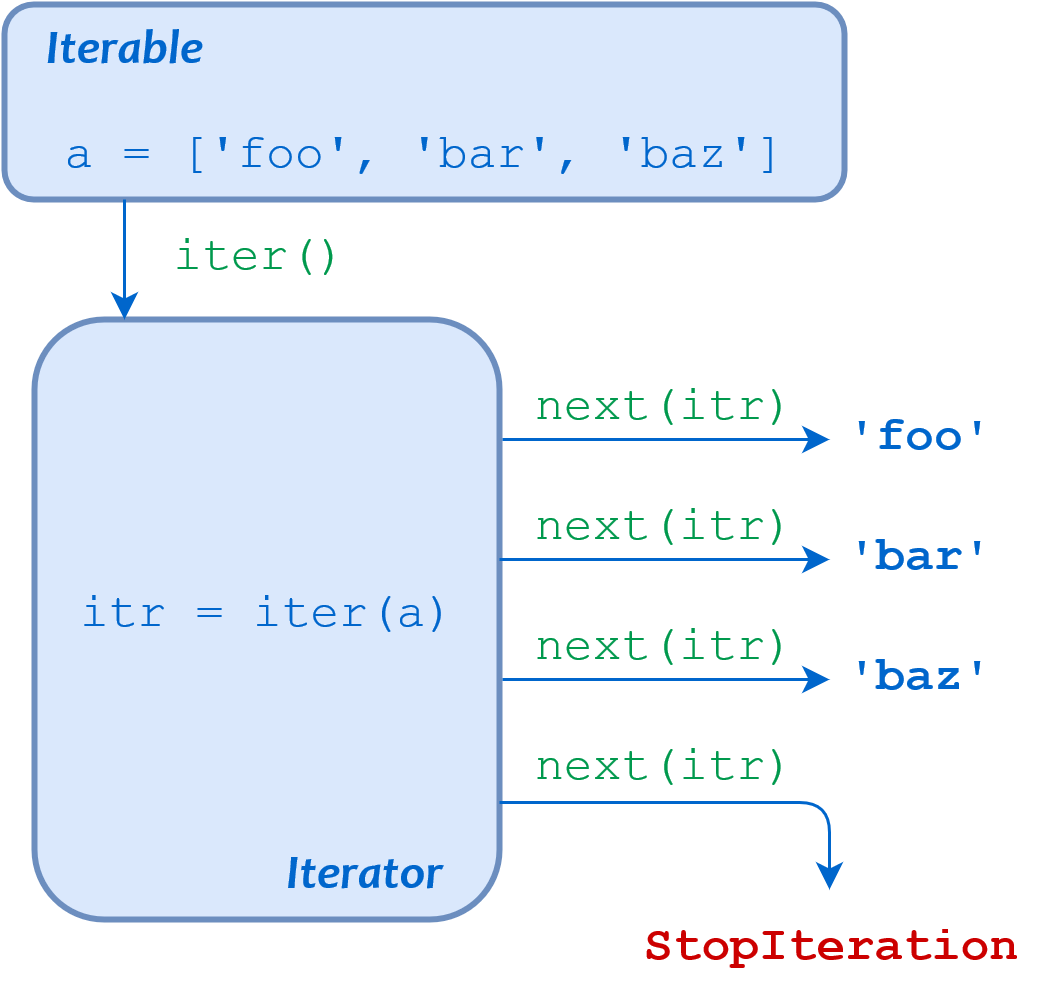

An iterator is essentially a value producer that yields successive values from its associated iterable object. The built-in office adjacent() is used to obtain the side by side value from in iterator.

Here is an case using the same listing as in a higher place:

>>>

>>> a = [ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' ] >>> itr = iter ( a ) >>> itr <list_iterator object at 0x031EFD10> >>> next ( itr ) 'foo' >>> next ( itr ) 'bar' >>> next ( itr ) 'baz' In this example, a is an iterable listing and itr is the associated iterator, obtained with iter(). Each adjacent(itr) phone call obtains the side by side value from itr.

Observe how an iterator retains its state internally. It knows which values have been obtained already, so when you phone call next(), it knows what value to return next.

What happens when the iterator runs out of values? Let'due south make ane more next() call on the iterator above:

>>>

>>> next ( itr ) Traceback (most contempo call last): File "<pyshell#10>", line 1, in <module> next ( itr ) StopIteration If all the values from an iterator have been returned already, a subsequent next() call raises a StopIteration exception. Whatever farther attempts to obtain values from the iterator volition neglect.

You can only obtain values from an iterator in 1 direction. Y'all tin't go astern. In that location is no prev() function. Simply y'all tin ascertain ii contained iterators on the aforementioned iterable object:

>>>

>>> a ['foo', 'bar', 'baz'] >>> itr1 = iter ( a ) >>> itr2 = iter ( a ) >>> adjacent ( itr1 ) 'foo' >>> next ( itr1 ) 'bar' >>> next ( itr1 ) 'baz' >>> next ( itr2 ) 'foo' Even when iterator itr1 is already at the terminate of the list, itr2 is still at the starting time. Each iterator maintains its ain internal state, independent of the other.

If you lot desire to catch all the values from an iterator at once, you can utilize the congenital-in list() function. Amongst other possible uses, list() takes an iterator as its argument, and returns a listing consisting of all the values that the iterator yielded:

>>>

>>> a = [ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' ] >>> itr = iter ( a ) >>> list ( itr ) ['foo', 'bar', 'baz'] Similarly, the congenital-in tuple() and set up() functions return a tuple and a set, respectively, from all the values an iterator yields:

>>>

>>> a = [ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' ] >>> itr = iter ( a ) >>> tuple ( itr ) ('foo', 'bar', 'baz') >>> itr = iter ( a ) >>> set ( itr ) {'baz', 'foo', 'bar'} It isn't necessarily brash to make a habit of this. Office of the elegance of iterators is that they are "lazy." That ways that when y'all create an iterator, information technology doesn't generate all the items it can yield simply then. It waits until y'all ask for them with next(). Items are not created until they are requested.

When you use listing(), tuple(), or the like, y'all are forcing the iterator to generate all its values at in one case, so they tin can all be returned. If the total number of objects the iterator returns is very large, that may take a long time.

In fact, it is possible to create an iterator in Python that returns an endless series of objects using generator functions and itertools. If you endeavor to grab all the values at in one case from an endless iterator, the program will hang.

The Guts of the Python for Loop

Y'all now have been introduced to all the concepts you lot need to fully empathize how Python's for loop works. Earlier proceeding, allow'due south review the relevant terms:

| Term | Pregnant |

|---|---|

| Iteration | The procedure of looping through the objects or items in a drove |

| Iterable | An object (or the adjective used to draw an object) that tin exist iterated over |

| Iterator | The object that produces successive items or values from its associated iterable |

iter() | The built-in function used to obtain an iterator from an iterable |

At present, consider again the elementary for loop presented at the start of this tutorial:

>>>

>>> a = [ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' ] >>> for i in a : ... print ( i ) ... foo bar baz This loop tin can be described entirely in terms of the concepts you lot have only learned most. To comport out the iteration this for loop describes, Python does the post-obit:

- Calls

iter()to obtain an iterator fora - Calls

next()repeatedly to obtain each detail from the iterator in turn - Terminates the loop when

side by side()raises theStopIterationexception

The loop body is executed once for each item side by side() returns, with loop variable i gear up to the given item for each iteration.

This sequence of events is summarized in the following diagram:

Perhaps this seems like a lot of unnecessary monkey business, but the benefit is substantial. Python treats looping over all iterables in exactly this way, and in Python, iterables and iterators abound:

-

Many built-in and library objects are iterable.

-

There is a Standard Library module called

itertoolscontaining many functions that return iterables. -

User-defined objects created with Python'due south object-oriented adequacy can be made to be iterable.

-

Python features a construct called a generator that allows you to create your ain iterator in a simple, straightforward fashion.

You will observe more about all the above throughout this series. They can all exist the target of a for loop, and the syntax is the aforementioned across the lath. It's elegant in its simplicity and eminently versatile.

Iterating Through a Lexicon

Y'all saw earlier that an iterator can be obtained from a dictionary with iter(), and so yous know dictionaries must be iterable. What happens when you loop through a dictionary? Let'southward come across:

>>>

>>> d = { 'foo' : ane , 'bar' : ii , 'baz' : 3 } >>> for grand in d : ... print ( k ) ... foo bar baz As you can meet, when a for loop iterates through a dictionary, the loop variable is assigned to the lexicon's keys.

To access the dictionary values within the loop, you tin can brand a dictionary reference using the key as usual:

>>>

>>> for k in d : ... print ( d [ yard ]) ... one 2 3 Yous can also iterate through a dictionary's values directly by using .values():

>>>

>>> for v in d . values (): ... print ( five ) ... 1 2 3 In fact, you can iterate through both the keys and values of a dictionary simultaneously. That is because the loop variable of a for loop isn't limited to only a unmarried variable. It can also be a tuple, in which case the assignments are made from the items in the iterable using packing and unpacking, just as with an assignment argument:

>>>

>>> i , j = ( i , 2 ) >>> print ( i , j ) 1 ii >>> for i , j in [( one , 2 ), ( iii , 4 ), ( v , 6 )]: ... impress ( i , j ) ... 1 2 3 4 5 6 Equally noted in the tutorial on Python dictionaries, the lexicon method .items() finer returns a list of key/value pairs as tuples:

>>>

>>> d = { 'foo' : one , 'bar' : 2 , 'baz' : 3 } >>> d . items () dict_items([('foo', ane), ('bar', 2), ('baz', 3)]) Thus, the Pythonic way to iterate through a lexicon accessing both the keys and values looks like this:

>>>

>>> d = { 'foo' : 1 , 'bar' : ii , 'baz' : 3 } >>> for k , v in d . items (): ... print ( 'g =' , k , ', v =' , 5 ) ... one thousand = foo , v = one k = bar , v = 2 g = baz , v = 3 The range() Office

In the first section of this tutorial, you lot saw a type of for loop called a numeric range loop, in which starting and ending numeric values are specified. Although this form of for loop isn't directly congenital into Python, it is easily arrived at.

For instance, if you wanted to iterate through the values from 0 to 4, you could simply exercise this:

>>>

>>> for due north in ( 0 , 1 , two , iii , 4 ): ... impress ( n ) ... 0 i two 3 4 This solution isn't as well bad when there are just a few numbers. But if the number range were much larger, information technology would get tedious pretty quickly.

Happily, Python provides a better option—the built-in range() function, which returns an iterable that yields a sequence of integers.

range(<end>) returns an iterable that yields integers starting with 0, up to just not including <terminate>:

>>>

>>> 10 = range ( 5 ) >>> x range(0, v) >>> type ( x ) <class 'range'> Notation that range() returns an object of class range, non a list or tuple of the values. Considering a range object is an iterable, you can obtain the values past iterating over them with a for loop:

>>>

>>> for n in x : ... print ( north ) ... 0 1 ii three iv You could also snag all the values at one time with list() or tuple(). In a REPL session, that can be a convenient way to quickly display what the values are:

>>>

>>> list ( 10 ) [0, 1, 2, 3, 4] >>> tuple ( x ) (0, ane, two, 3, 4) Withal, when range() is used in code that is function of a larger awarding, information technology is typically considered poor practice to apply listing() or tuple() in this way. Like iterators, range objects are lazy—the values in the specified range are not generated until they are requested. Using listing() or tuple() on a range object forces all the values to be returned at one time. This is rarely necessary, and if the list is long, it tin can waste time and memory.

range(<brainstorm>, <end>, <stride>) returns an iterable that yields integers starting with <begin>, upward to but not including <finish>. If specified, <stride> indicates an corporeality to skip betwixt values (analogous to the stride value used for string and listing slicing):

>>>

>>> listing ( range ( 5 , 20 , 3 )) [5, viii, 11, 14, 17] If <pace> is omitted, it defaults to 1:

>>>

>>> list ( range ( 5 , 10 , ane )) [5, 6, 7, 8, nine] >>> listing ( range ( 5 , 10 )) [5, 6, vii, 8, ix] All the parameters specified to range() must exist integers, just whatever of them tin can be negative. Naturally, if <begin> is greater than <end>, <stride> must exist negative (if you want any results):

>>>

>>> list ( range ( - 5 , 5 )) [-5, -iv, -3, -2, -i, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4] >>> list ( range ( 5 , - 5 )) [] >>> list ( range ( 5 , - 5 , - 1 )) [five, iv, 3, two, 1, 0, -1, -2, -3, -iv] Altering for Loop Behavior

You saw in the previous tutorial in this introductory series how execution of a while loop can exist interrupted with interruption and go along statements and modified with an else clause. These capabilities are available with the for loop too.

The intermission and continue Statements

pause and continue work the same way with for loops as with while loops. break terminates the loop completely and proceeds to the beginning statement following the loop:

>>>

>>> for i in [ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' , 'qux' ]: ... if 'b' in i : ... interruption ... print ( i ) ... foo continue terminates the electric current iteration and proceeds to the adjacent iteration:

>>>

>>> for i in [ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' , 'qux' ]: ... if 'b' in i : ... continue ... print ( i ) ... foo qux The else Clause

A for loop tin have an else clause as well. The interpretation is coordinating to that of a while loop. The else clause volition be executed if the loop terminates through exhaustion of the iterable:

>>>

>>> for i in [ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' , 'qux' ]: ... print ( i ) ... else : ... print ( 'Washed.' ) # Will execute ... foo bar baz qux Done. The else clause won't be executed if the list is broken out of with a break argument:

>>>

>>> for i in [ 'foo' , 'bar' , 'baz' , 'qux' ]: ... if i == 'bar' : ... break ... impress ( i ) ... else : ... impress ( 'Washed.' ) # Will non execute ... foo Conclusion

This tutorial presented the for loop, the workhorse of definite iteration in Python.

You besides learned virtually the inner workings of iterables and iterators, two of import object types that underlie definite iteration, but also figure prominently in a wide variety of other Python lawmaking.

In the next ii tutorials in this introductory series, you will shift gears a niggling and explore how Python programs tin can interact with the user via input from the keyboard and output to the console.

Sentinel Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python squad. Sentry it together with the written tutorial to deepen your agreement: For Loops in Python (Definite Iteration)

Source: https://realpython.com/python-for-loop/

Post a Comment for "What Is the Quantity Arrived at an Iteration Do Again"